I have accidentally fallen into an autobio comics hole; over the last week or so, I went from Dustin Harbin’s Diary Comics to John Porcellino’s The Hospital Suite before landing back in the middle of a longterm favorite, Eddie Campbell’s Alec, all without really realizing what was going on. Okay, that’s not entirely true; I went back to Alec in large part because the combination of the first two left me more conscious of what does, and doesn’t work for me in terms of people telling their life stories in comics. I ended up returning to the best, in my opinion, to recharge and restore my faith in my taste, as ridiculous as that sounds.

Diary Comics and The Hospital Suite feel like exercises in comparisons, in terms of approach to autobio — one intentionally filled with short, meaningless vignettes that, almost accidentally, build to a greater picture of their creator, while the other is positioned more as a conventional long form narrative (Actually, three long form narratives, that co-exist and co-mingle in terms of timeframes) about interrelated topics. They’re both perfect illustrations of their respective creators’ obsessions and temperaments, as well; the neuroses that both have about their places in the world and making themselves heard.

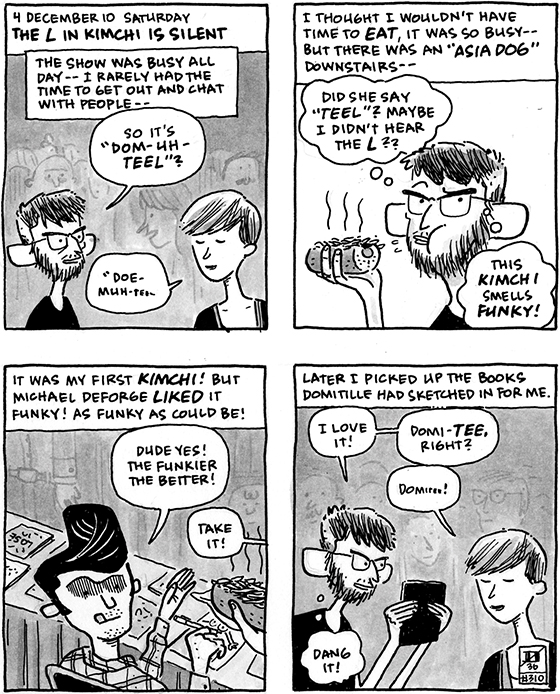

Of the two, I much preferred Diary Comics; part of it is, I suspect, generational — Harbin and I are the same age (or thereabouts, at least), and I felt as if I shared many of his preoccupations about life. We also share a similar sense of humor, which is one of the major ways in which Diary hit for me where Hospital didn’t; the latter is an amazingly sincere, almost humorless book, whereas Diary Comics is, for all intents and purposes, a humor strip for at least half of its run. That’s one of its strengths; the recurring themes are given space to arise naturally, as Harbin just tries to record and entertain, instead of make A Point, which he avoids until the (wonderful, pitch-perfect) coda to the book, “Boxes.”

Of the two, I much preferred Diary Comics; part of it is, I suspect, generational — Harbin and I are the same age (or thereabouts, at least), and I felt as if I shared many of his preoccupations about life. We also share a similar sense of humor, which is one of the major ways in which Diary hit for me where Hospital didn’t; the latter is an amazingly sincere, almost humorless book, whereas Diary Comics is, for all intents and purposes, a humor strip for at least half of its run. That’s one of its strengths; the recurring themes are given space to arise naturally, as Harbin just tries to record and entertain, instead of make A Point, which he avoids until the (wonderful, pitch-perfect) coda to the book, “Boxes.”

“Boxes” is the epilogue, done after the fact and with some reflection on what’s come before; at least, that’s what it feels like. More expansive and considered that everything else in the book, it’s also more uncertain and vulnerable, Harbin taking advantage of the goodwill he’s built up with the reader to go on tangents and open up. The navel gazing has more weight because Harbin feels more real, more like a friend, because of what’s come before; it hits home in a way that it didn’t even in its earlier release as a standalone mini-comic (which I also loved; there’s just some great cartooning on show, in addition to the existential exploration that recalls Kevin Huizenga at times).

The Hospital Suite, on the other hand, fell flat for me in a number of ways. Ultimately, I don’t think I’m a fit for Porcellino’s work; I recognize its appeal, without finding it appealing — it’s without artifice or artistry, which can have an outsider honesty for those who want to see that. For me, though, I found it tiring; Porcellino isn’t one for reflection outside of a very narrow, very adolescent focus (For someone so myopic when it comes to his buddhist beliefs, he’s almost ironically selfish and self-obsessed), and prefers to tell his stories in a very linear, this happened, then this happened, then this happened format that becomes tiring over an extended period, moreso when so much of the content is so repetitive.

The Hospital Suite, on the other hand, fell flat for me in a number of ways. Ultimately, I don’t think I’m a fit for Porcellino’s work; I recognize its appeal, without finding it appealing — it’s without artifice or artistry, which can have an outsider honesty for those who want to see that. For me, though, I found it tiring; Porcellino isn’t one for reflection outside of a very narrow, very adolescent focus (For someone so myopic when it comes to his buddhist beliefs, he’s almost ironically selfish and self-obsessed), and prefers to tell his stories in a very linear, this happened, then this happened, then this happened format that becomes tiring over an extended period, moreso when so much of the content is so repetitive.

(I feel bad writing that; a lot of The Hospital Suite revolves around Porcellino’s recurring health problems, and I feel that complaining about repetition or it being dull feels like I’m essentially writing “Your sickness is boring”; I’m not meaning that at all. In fact, the reason I kept reading was a hope that he’d find a solution to his problems, despite the way that he told the story.)

It’s interesting; so much of Harbin’s work is obsessed with how the world views him, whereas Porcellino seems utterly oblivious to that. There’s a part of the book where his wife leaves him, and it comes utterly out of the blue for him, despite the fact that’s it’s been clear to the reader that he’s not been taking her feelings or experience into account outside of how it directly affects him up to that point; it’s the most obvious moment of a lack of curiosity that’s shot through the entire book.

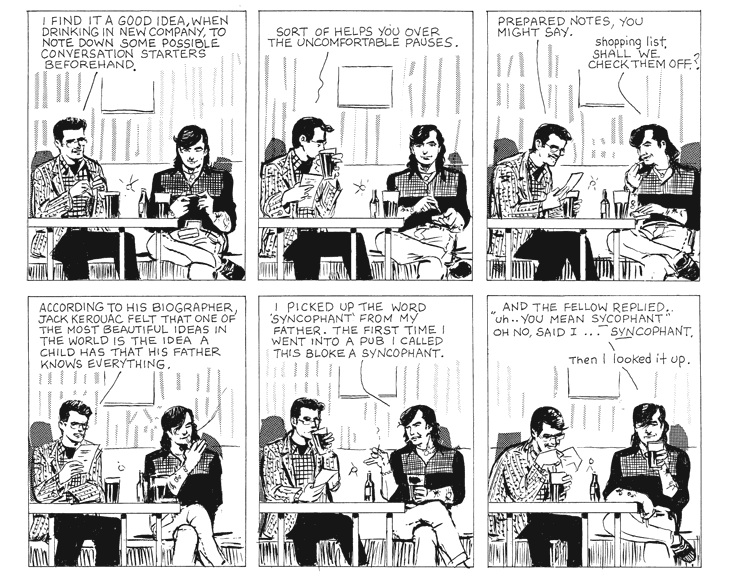

In many ways, it was that element of Hospital that drove me back to Alec. Campbell’s stories manage to present a lead as self-obsessed and unaware as Porcellino, but in a way that allows everyone around him a life of their own, and an existence outside of being props for “our hero.” There’s a humility (and humanity?) on show that I found lacking in The Hospital Suite, but also an extended narrative experience and ambition that isn’t present in Diary Comics, due to its format.

It’s simplistic to describe Alec as some kind of precognitive melding of the two, but re-reading it after the earlier two books, I kept thinking about all three in terms of food; whereas Diary Comics and The Hospital Suite were snacks of varying degrees of tastiness, Alec is a full meal, a greater undertaking created with different intent that nonetheless ends up satisfying all the cravings the earlier two created, and then some.