Continuing my Crisis on Infinite Earths thoughts, which began yesterday, as I try to make up for missing a written post last week.

It took me maybe three attempts at reading Crisis on Infinite Earths before I recognized the story in it. I mean, I’m not an idiot; I’d always gotten the meta-story, the whole “Oh no, reality is ending and by reality I mean the old school DC continuity” part of things, but the problem has been that that had been too loud, too overwhelming. I’d ended up focusing on that aspect — shit, now they’ve crippled Ted Grant, is anyone safe? — and losing track of what else Marv Wolfman was doing in the series. In my defense, Wolfman clearly does the same thing the longer the series continues.

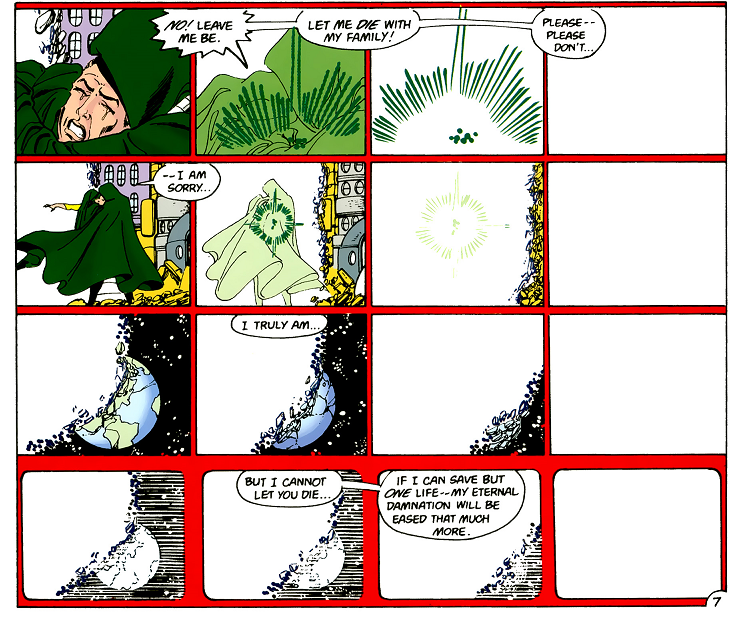

But inside that, in between the bigger, more cosmic moments of Crisis, there’s something else going on — stories about characters that actually “belong” to the series, and aren’t just borrowed for star power, like Lyla, Pariah, Lady Quark and the Psycho Pirate. (It’s not a series about either the Monitor nor the Anti-Monitor, who is clearly intended to be a relatively faceless threat, although he gets a couple of costumes and an issue of expeditionary backstory nonetheless; something I like about Crisis‘s scope is that, before things get all-too-busy in the back third, it has time to do things like that.) There are emotional journeys underway, even if all of them end up getting shorthanded or abandoned as Wolfman starts to drown in the book’s larger, editorial purpose.

Actually, now that I’ve nodded in that direction a couple of times, I should just say it outright; as great as Crisis is as an event comic — and I genuinely think it’s one of the best, with an argument to be made for being the best when you factor in that it was breaking this ground as it went on — it falls apart in the final act. There’s so much to be achieved in the final issues on a couple of probably-more-important-to-editorial levels (establishing the new DCU status quo, setting up the tie-in issues) that the more personal stories that Wolfman has been trying to tell get shortchanged, and events just pile up on themselves — or worse, happen off-panel — which effectively deadens their impact. As much as I doubt that either Wolfman or Perez would’ve welcomed the suggestion at the time they were working on the book, it feels like it needed another issue to properly stick the landing.

But even with that caveat in place, Crisis is a remarkably complete, surprisingly subtle piece of work at times. Lyla — who, notably, is definitively not Harbinger for all intents and purposes until late in the book where she has powers and adopts the identity for reasons unexplained because there’s no time — Lady Quark and Pariah, unusually for event book introductions, all have emotional journeys and agency in and of themselves. The Psycho Pirate, arguably, becomes the focus point for he book’s big events in his journey (and weirdly echoes what Jim Shooter does with Klaw in Secret Wars to an extent. Hrm). There’s a throughline for the series that isn’t just “And then this big thing happens, and then this, and then this! LOSE YOUR MINDS, FANBOY!”

Of course, there are those moments as well; the death of the Flash and Supergirl are played up for all they’re worth, and it’s difficult to imagine how they felt at the time, when they probably did seem legit and not something that would be undone soon enough. (We’re too cynical to fall for such things now, of course, having seen what we’ve seen; imagine how it would feel otherwise, though!) Similarly, doing away with the multiple Earths in and of itself seems daring and unknown in a way that feels difficult to properly imagine these days.

And, of course, all of this — a comic that really ensuring that everything you knew was wrong, or at least, in danger — was being done by the creative team that really was DC’s biggest at the time. Imagine the excitement if DC announced an event comic by Snyder and Capullo now for a rough comparison. (Actually, when was the last time such a thing happened, at DC, at least? Blackest Night with Geoff Johns and Ivan Reis? For all that Secret Wars was being hyped up as the biggest thing since sliced bread, it’s worth remembering that Hickman’s Avengers wasn’t Marvel’s biggest book, and even so, he didn’t even have a constant artistic partner on that book.)

Perez’s work on the title is career-making, of course. It’s stronger than his New Teen Titans work that he’d been handling prior to this, in part because of the schedule and the demands; there are things — character acting, sheer volume of characters — that he chooses to concentrate on, while some of his detail work falls by the wayside, and the end result is more attractive, bolder. The choice of inkers help with this, too; Ordway brings a weight to the pencils that Romeo Tanghal and Dick Giordano didn’t on Titans, and I suspect that some of the convincing aging of characters is down to Ordway’s inks, more than Perez’s pencils (I could be wrong, mind you).

It feels like a strange thing to say about a comic that’s generally regarded as a groundbreaking classic that it’s better than expected, but in Crisis‘s case, it’s true. Crisis on Infinite Earths has its reputation because of the effects that it had on the greater DC Universe and continuity, and because George Perez drew so many fucking characters. But underneath all of that, it turns out to be a surprisingly strong superhero comic in its own right.

If only the same could be said about the second and third parts of what ended up being the Crisis trilogy.

I read Crisis when it was originally published back in 1985 and reading it monthly gave a better feel for the character arcs you mentioned, as well as things falling apart in the last quarter. At the time I thought it became increasingly repetitious, and have since learnt that was down to the original ending being hived off to form the Guide to the DC Universe and Wolfman and Perez having to give us multiple defeats of the Anti-Monitor as a replacement.

I was in my mid teens in the mid 80’s, and Crisis was one of my three gateway drugs into the DC Universe, following Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and contemporaneous with Ambush Bug. They all introduced me to the colourful world of DC Superheroes after a childhood where the availability of superheroes was through Marvel UK’s black and white reprints. Which goes to show if a mega crossover event is well enough crafted then it can be used to gain new readers, no matter how unfamiliar they may be to that world (or multiverse in this case).

Interestingly enough, I read the Marvel UK reprints of Secret Wars shortly after the first few issues of Crisis and thought it a shallow imitation of the later, with far inferior art and a tone deafness to most of the characters I’d known from the earlier mentioned Marvel UK reprints.

I’ve never fully understood why Crisis fell out of favour, although as Graeme said in part one, that may have had something to do with the lack of reprints for such a long time. always strange considering how on the ball DC were with their collected additions.

For some purely anecdotal perspective: most of my friends and I were intensely skeptical at the time that these deaths would stick. Jean Grey came back from the dead while Crisis was running, and it wasn’t exactly the first time we’d seen “no, no, totes dead, you betcha” deaths undone. Captain Marvel was staying dead, but lots of others who’d died in the decade and some we’d been reading comics hadn’t.

There was, admittedly, the possibility that the sheer weight of Crisis as a whole meant that things would stick this time.

I feel for the hype about the “never ever reprinted again” CRISIS hardcover, too, Graeme. Ya ain’t alone.

CRISIS is, to me, and I think I described it this was after reading the collection the first time that it was a lot like that Looney Tunes cartoon where Daffy Duck blows himself up to upstage Bugs Bunny, and while it does, Daffy is deader than dirt shrugging “I can only do it once.”

The problem with these kinds of stories is that you can blow up 50 years of continuity and bring it back all day long, but what’s you’ve made the separation that none of it counts for very much, then it’s just moving stuff around.