Previously on Baxter Building: Steve Englehart arrived, and immediately changed things forever (Really, about twenty issues, but still) by sending Reed and Sue off to domestic bliss in Connecticut and bringing in two new members of the team: Ms. Marvel (Sharon Ventura; Kamala Khan wouldn’t be created for another quarter of a century) and Crystal of the Inhumans. As if the soap operatics of that shift wasn’t enough, Ms. Marvel and the Thing flew through more cosmic rays, and became She-Thing and Even-Thingier, respectively, leading to an issue where one character kept trying to kill themselves repeatedly. (No, really; she got better.) Meanwhile, Doctor Doom is still out there, waiting to cause trouble. Spoilers: He’s about to cause trouble.

0:00:00-0:10:49: After an extended cold open in which Jeff complains about the lack of visual appeal to the current incarnation of the Fantastic Four — by which I mean, the ones we’re covering, not the current incarnation, 2017-style, because there isn’t one — we talk about the issues we’re going to cover and accidentally lie to you. We really meant to cover Fantastic Fours #314-324 and Annual #21, but… well, we just weren’t up to the task. We only make it as far as #321, and even that was a struggle, as you’ll hear.

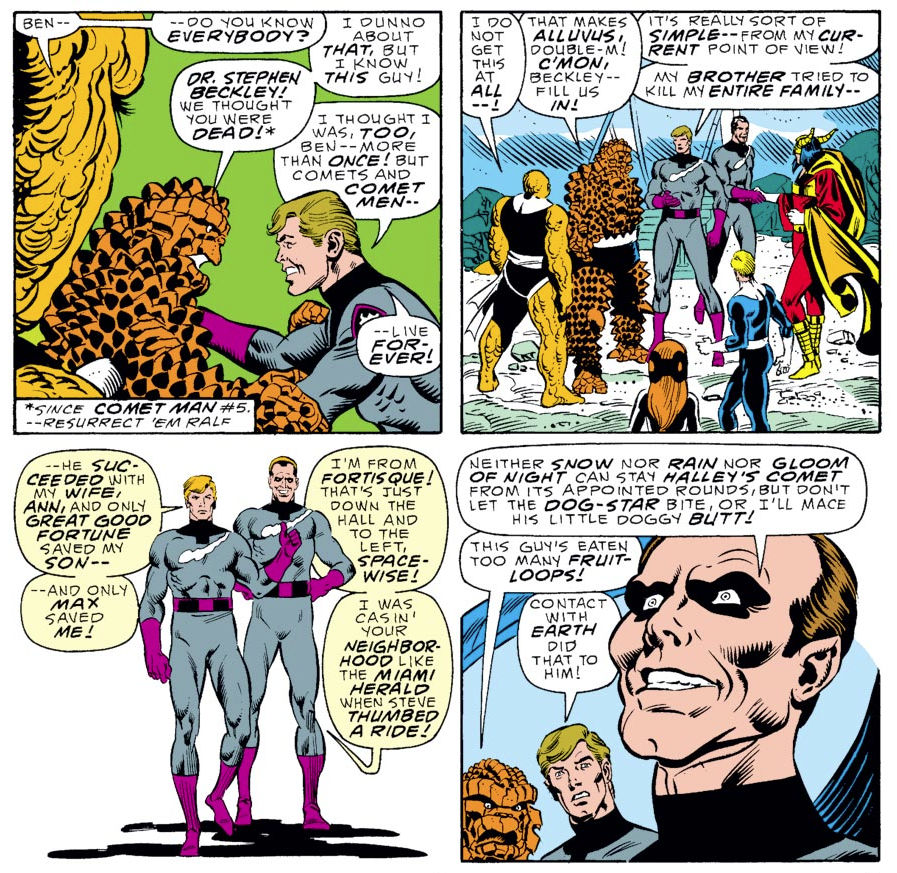

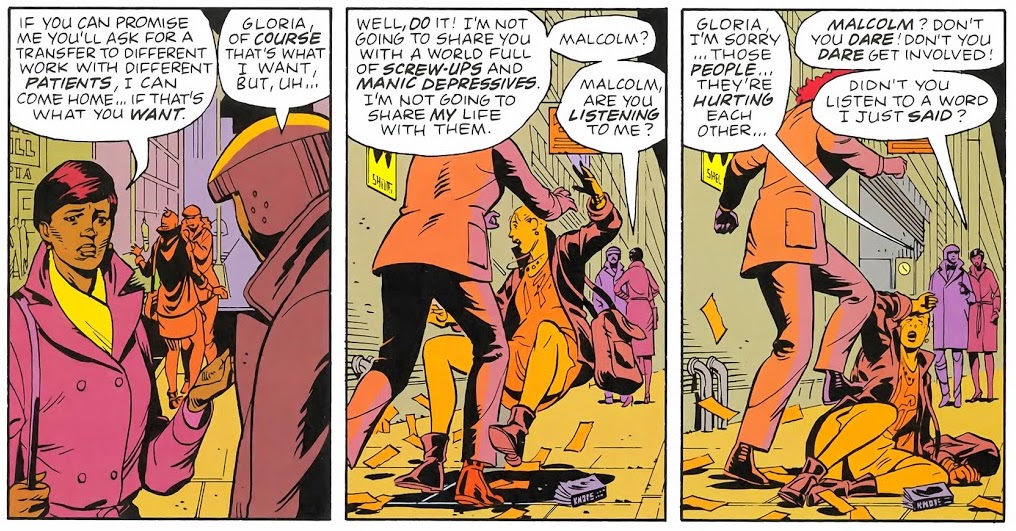

0:10:50-0:31:19: We begin with Fantastic Four #314 and #315, in which the team gets lost and only finds a way home through the kindness of strangers who just so happen to take over their comic book, kind of. Jeff and I talk about the appeal of the Thing as the center of the Marvel Universe, the “Emotional Dysfunction Engine” that is Johnny’s relationship with himself and the slightly shifting, kind of repeating monologues it includes, and whether or not the series fulfills the promise of the Lee and Kirby era, despite barely resembling it. As Jeff puts it, there two issues are “an amazingly off-kilter read” that break “so many rules and probably John Byrne’s heart,” and if that isn’t the best pull-quote, what is?

0:31:20-0:52:27: FF #316 explains the secret history of the parts of the Marvel Universe you never cared about, but does it matter without the emotional through line to keep the reader engaged? We discuss that, because I liked what happens in the second half of this issue far more than Jeff did. Also, we get into the FF as passive participants in their own comic, the very ideal of what it means to be the Fantastic Four in the first place (and whether Steve Englehart has a different idea of what it means to be heroic than contemporary writers), and Jeff raises the idea of an Englehart version of Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, which still blows my mind a little.

0:52:28-1:05:31: By the time we get to Fantastic Four #317, it’s time to talk about Alicia and Johnny’s relationship and whether or not it’s a believable one, especially given the awkward bit at the start that Jeff is sold on, and I’m not. Other topics of discussion: Alicia as being the emotionally mature one in the Ben/Alicia/Johnny bizarre love triangle, the strange notion that AIM apparently works in intergalactic currency, and what happens when Steve Englehart has an enemy… and it’s Steve Englehart! (No clones were involved with the creation of this comic, to the best of ur knowledge.)

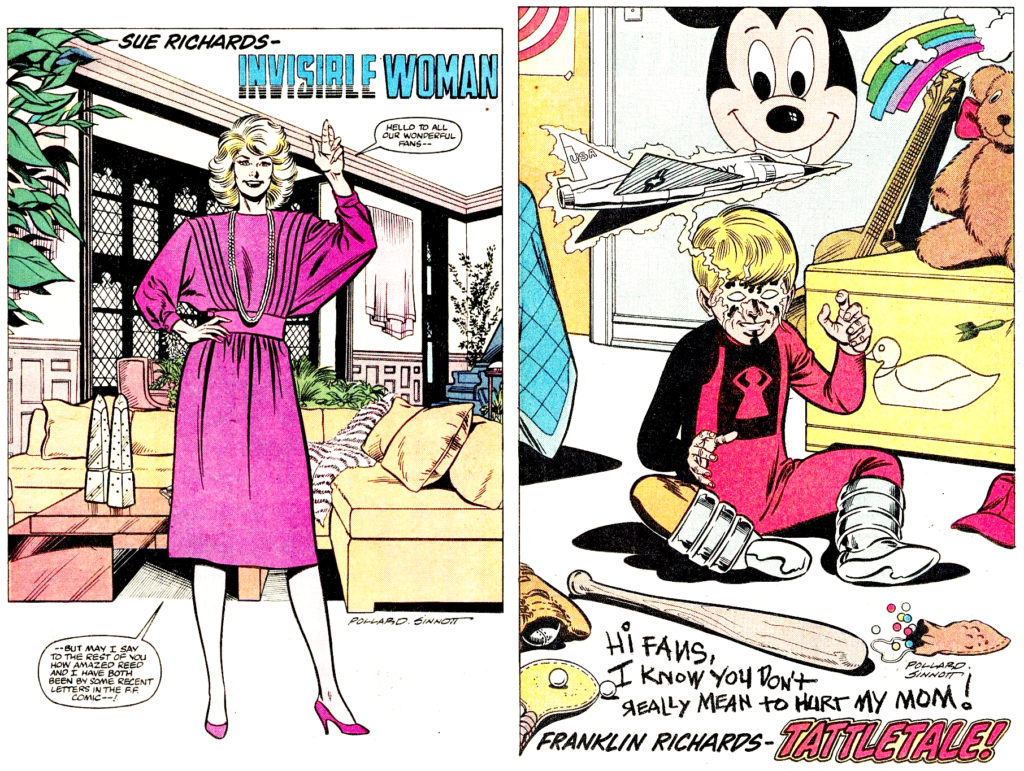

1:05:32-1:23:50: As we careen into FF Annual #21, we talk about the strange stuttering effect of these issues and how “Wait, how the fuck did we get here?” works as a hook to get readers interested in each issue. Meanwhile Crystal leaves the team, Quicksilver returns to the series (and leaves both of us confused about an apparent rehabilitation that neither of us believe), Steve Englehart becomes Jim Shooter in the strangest way possible, and there are the finest pin-ups any comic has ever displayed. No, really:

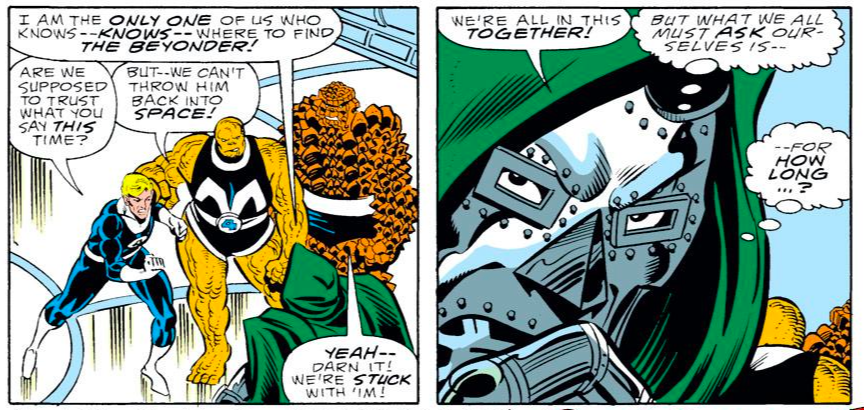

1:23:51-1:31:19: Doctor Doom arrives in Fantastic Four #318 and everything immediately gets better. What is the best thing about Doctor Doom? Jeff and I pretty much agree it’s his seeming inability to stop himself betraying everyone around him even when he really doesn’t need to. (As Jeff points out, this might make Master Pandemonium smarter, but Doctor Doom is still far cooler.) Plus, Blastaar returns and he’s taken care of so quickly, it’s as if Steve Englehart and Keith Pollard understand how shit he is.

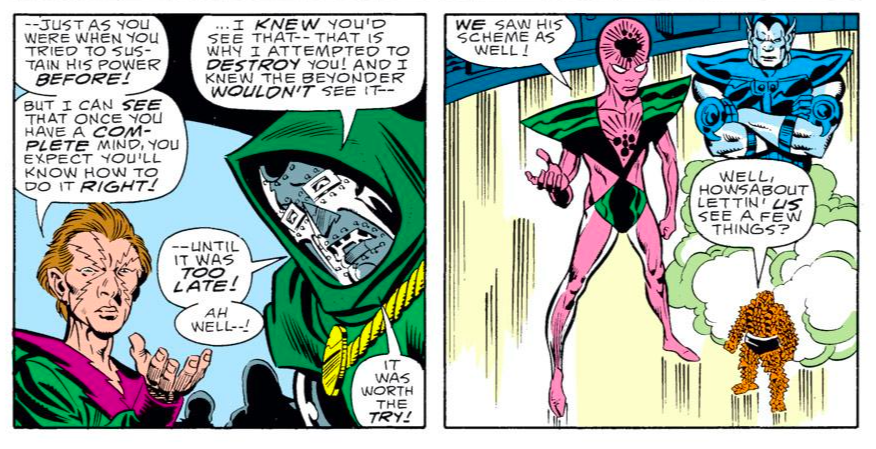

1:31:20-1:47:47: Is FF #319 — which is really called Secret Wars 3 — a better ending for the Beyonder than Secret Wars II? I certainly thought so when I was 13 years old, and knew no better. The story of the Beyonder gets a particularly Englehartian wrap-up that also includes the Molecule Man, as Jeff and I discuss philosophy, Millennium and the nature of existence, as you do. Oh, and we decide that we have to just ditch the last three issues were going to cover, because it’d taken us this long to do these ones. We’re only human, Whatnauts. Sorry.

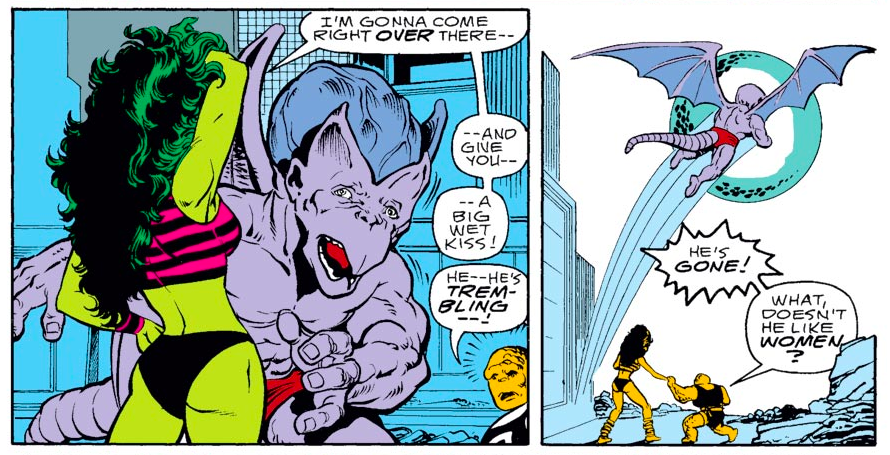

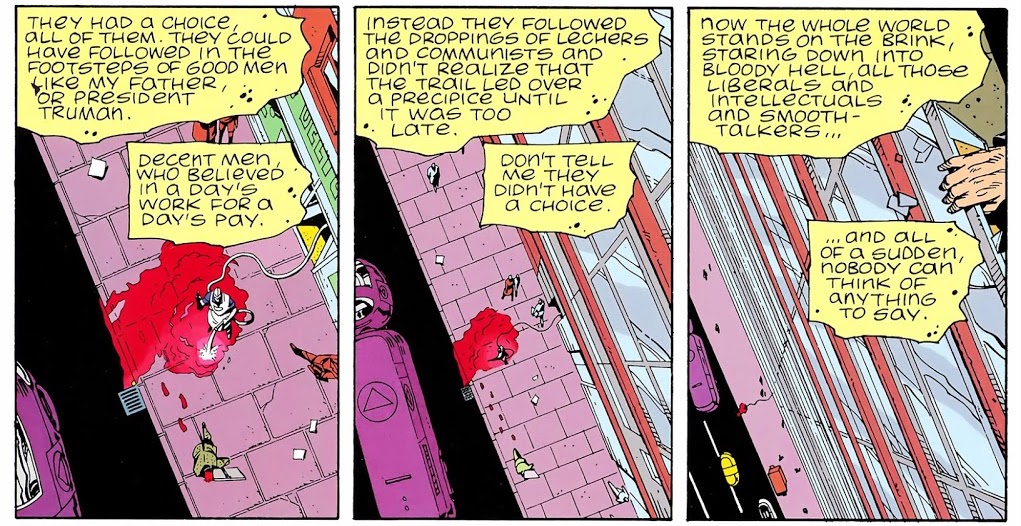

1:47:48-2:01:01: From the sublime to the ridiculous, and the one-two punch of Fantastic Four #320 and 321, in which the Thing fights the Hulk, and then Ms. Marvel fights the She-Hulk… kind of. Jeff’s into one of these issues, but I didn’t really enjoy any, in part because it seems like Englehart is producing these stories under duress. (Also, #321 is just terrible, and gets us talking about the difference between John Byrne’s She-Hulk and Steve Englehart’s, and why Byrne’s might be… better…? Nobody wants to hear that, not even us.)

2:01:02-end: We look ahead to what’s coming in the future briefly, and remind you all how tired we were when we recorded this. No, wait, I mean, we remind you all about our Tumblr, Twitter and Patreon. In a month, we return hopefully somewhat rested for Fantastic Four #s 322-327, which might mean a shorter episode for once. (Who am I kidding?)

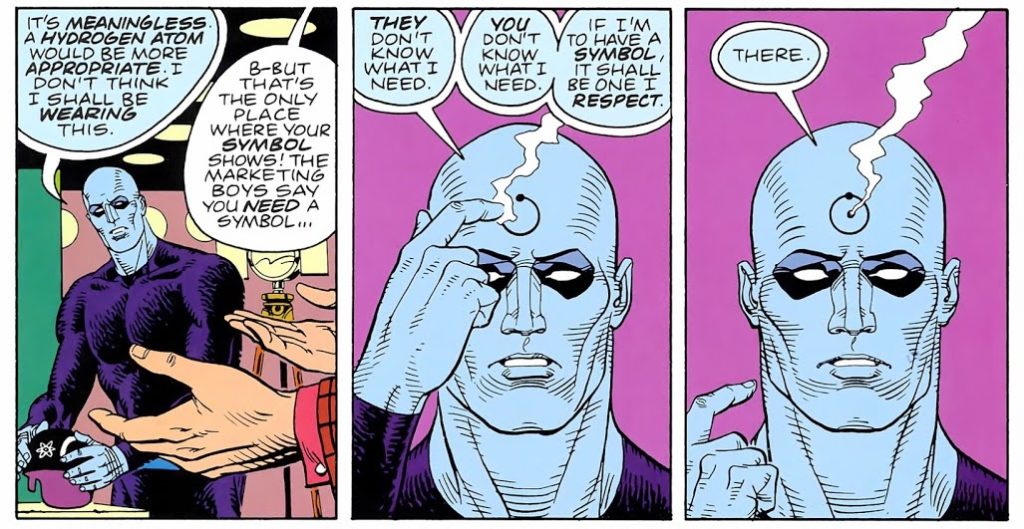

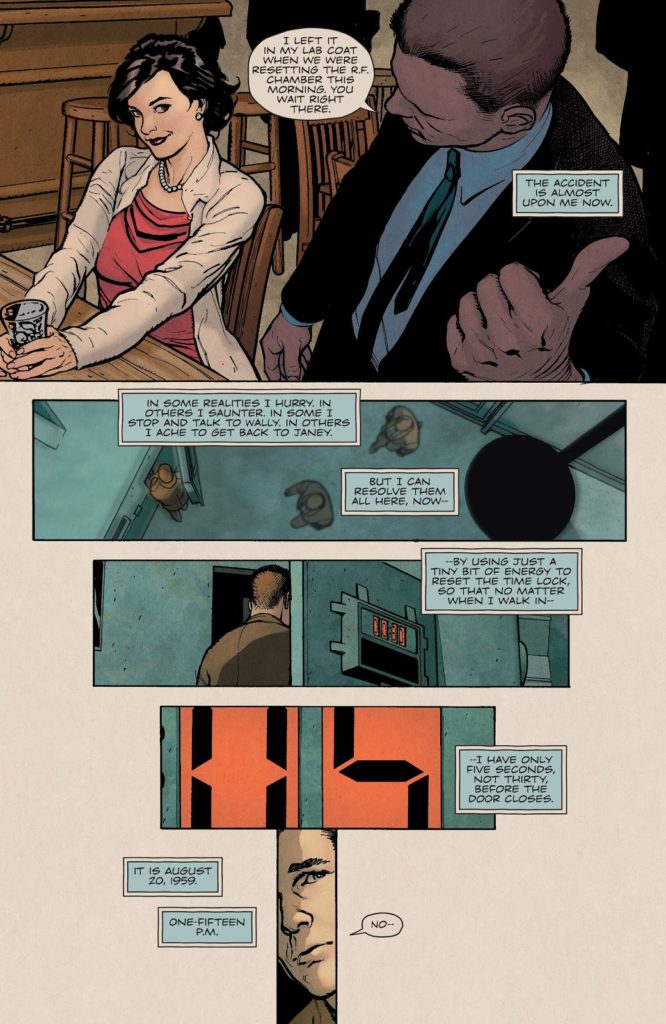

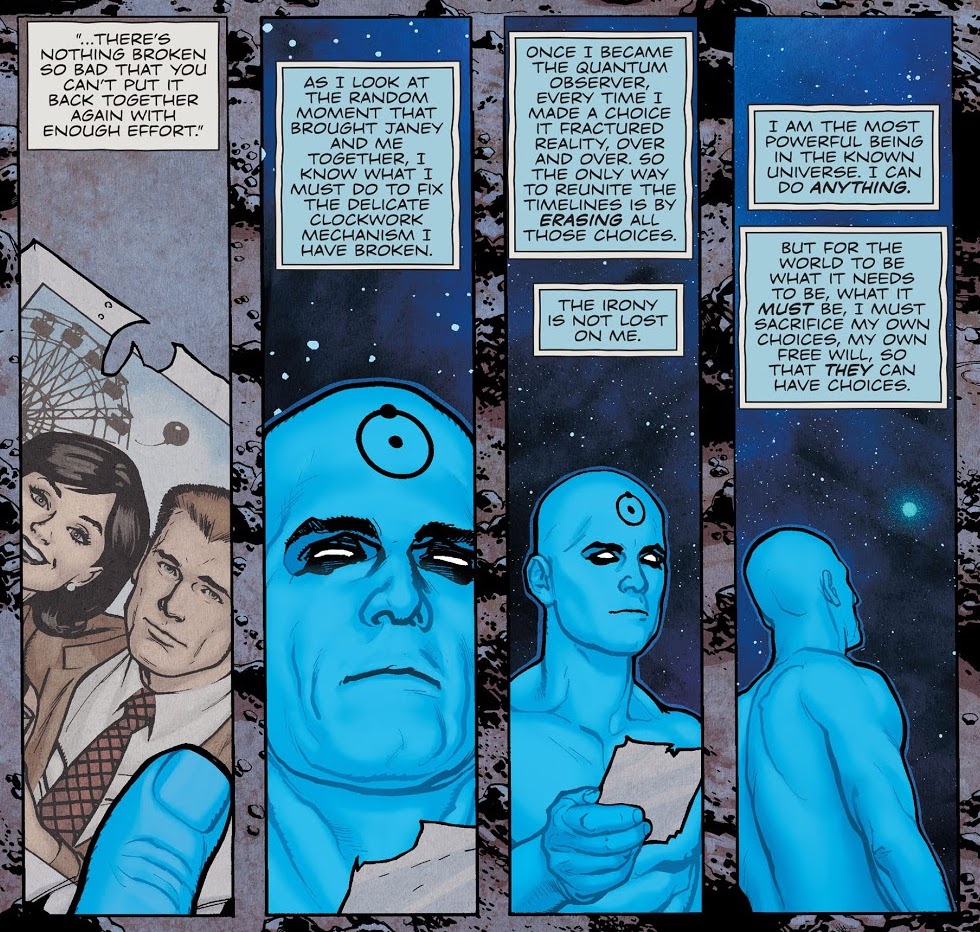

The gimmick of the series, so to speak, is that Dr. Manhattan, to quote Kurt Vonnegut, has become unstuck in time. Or, more properly, he unsticks time; in revisiting his past during the first issue of the series, he revisits the moment he went from Jon Osterman to Dr. Manhattan, only to discover that it doesn’t happen.

The gimmick of the series, so to speak, is that Dr. Manhattan, to quote Kurt Vonnegut, has become unstuck in time. Or, more properly, he unsticks time; in revisiting his past during the first issue of the series, he revisits the moment he went from Jon Osterman to Dr. Manhattan, only to discover that it doesn’t happen.

Recent Comments