Welcome to the year 2099, where the law is everything, and one man is the law — even if, in the stories we’re reading in this first episode of Drokk!, Judge Dredd isn’t exactly the fearsome lawman that everyone will come to know and love just yet. But watching how that happens is half the fun, or at least, half the fun of this podcast.

0:00:00-0:02:09: We roll into town — well, Mega-City One — with new music, courtesy of Mr. Jeffrey Lester, and introduce ourselves as well as what we’re actually reading this episode: Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 1, which covers 2000 AD Prog 2 – 60, from 1977 and 1978.

0:02:10-:0:04:59: Jeff quickly unpacks his history with Judge Dredd as a character and a strip, including mention of the Eagle Comics reprints that debuted in the U.S. in the early ‘80s. A quick correction to what I said in the show itself: The Eagle Comics reprints launched in 1983 as an offshoot of Titan Books, insofar as they were owned by the same man, Nick Landau. (There are probably many U.S. fans who’ll be familiar with the later Quality Comics reprints, which were like the Eagle reprints if done by someone who had access to a photocopier that destroyed page ratios and were colored by someone in a rush; the Eagle reprints were generally higher quality, and had original covers from Brian Bolland and other 2000 AD artists.)

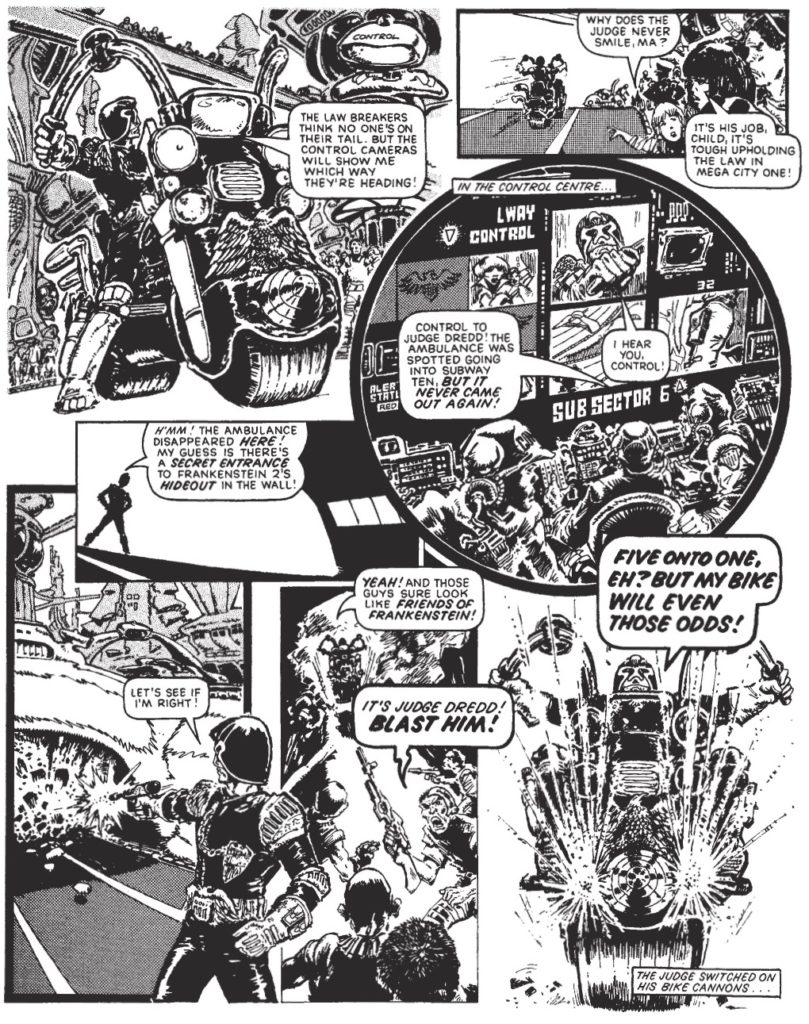

0:05:00-:0:15:03: We talk about the way in which the early years of Judge Dredd are different from the character and strip we know today, which is another way of saying, “Man, these early strips are often pretty goofy.” They’re also just burning through ideas, as if no-one behind the scenes really expecting Dredd to stick around that long and saw no reason to pace themselves.

0:15:04-0:23:01: “So much of this first volume feels born of desperation,” I say about the first year of the character, in which various writers and artists try and fill the void of Dredd after the immediate departure of his creators for reasons Jeff alludes to. (He’s referencing material from both Pat Mills’ Be Pure! Be Vigilant! Behave!: 2000 AD & Judge Dredd: The Secret History and also the wonderful Thrill-Power Overload: 2000 AD — The First Forty Years at times throughout this episode, starting here.)

0:23:02-0:31:36: We begin to get into the weeds, talking about potential influences in the earliest days of the series, whether that happens to be Silver Age DC Comics or the density of storytelling in earlier British comics that preceded 2000 AD altogether, while also touching on the difference in comics language between UK and US comics a little. (This, I suspect, will be something we’ll come back to a lot across this series as a whole.)

0:31:37-0:40:14: After a rough start, things start to fall into focus a bit more with the arrival of co-creator John Wagner on the strip, nine episodes in. (Yes, that seems to make little sense; we explain it, honest.) If nothing else, he’s the first writer who seems to be okay not only not trying to make Dredd heroic, but just the opposite: Understanding that Dredd works really well as a character without any great depth, or any noticeable sympathetic features. Oh, and also as kind of a bastard, too.

0:40:15-0:50:19: Mention of Walter the Wobot gets us onto the topic of sidekicks and their place in comic book tradition, as both Walter and, to a lesser extent, housekeeper Maria, are placed in a spectrum of characters that includes both Woozy Winks and Dennis the Menace’s Walter the Softy. (That’s the British Dennis, I should make clear.) Also! What is with John Wagner and racist stereotypes when it comes to sidekicks, and does Dredd being so unsympathetic make the racism somehow more palatable?

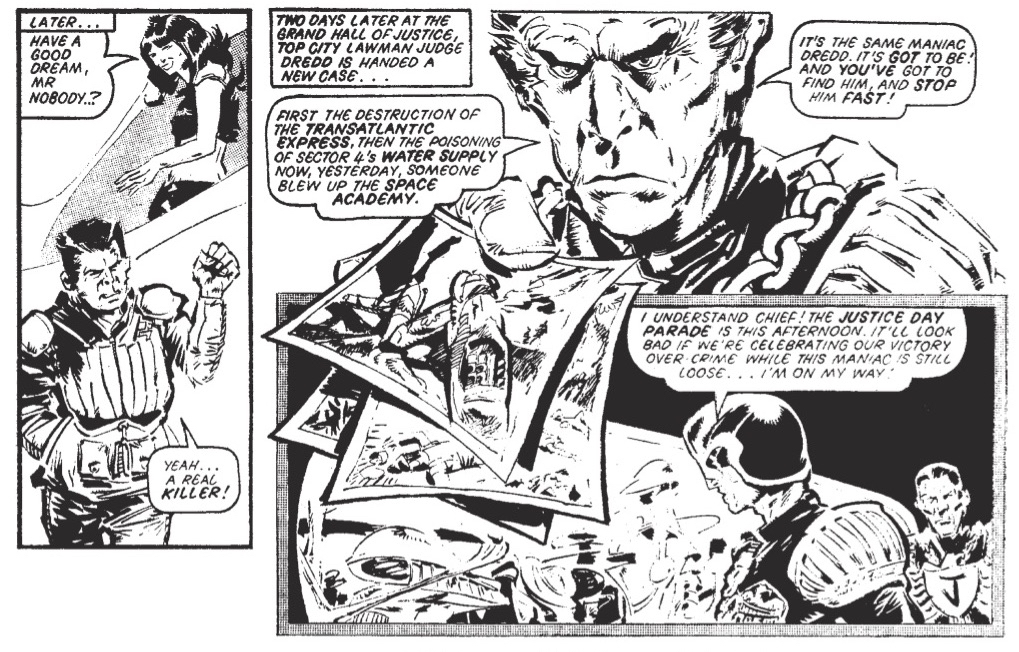

0:50:19-0:57:44: “The Return of Rico” marks Pat Mills’ greatest contribution to the series to date, and it’s a story packed with all kinds of great stuff that also happens to be ruined by a particularly terrible punchline. How did the Hollies get in here? Also! Jeff’s love of sentimental pop — revealed!

0:57:45-1:14:10: Rico’s debut isn’t the only bit of world building that stuck around from the second six months of the character’s existence, and we talk about the fact that John Wagner (and, to a lesser extent, others) seem to find their footing after a shaky start. This leads into a very brief diversion about Wagner working through different comic book crime influences as he tries to work out what kind of comic Judge Dredd is, especially — as far as I’m concerned — Will Eisner’s The Spirit.

1:14:11-1:21:16: “We haven’t talked enough about the art,” I say, and considering this book features Mike McMahon, Brian Bolland, Ian Gibson and many more, that’s a particular oversight we try to address here. Of note: Jeff loves Ron Turner’s work but isn’t a fan of early Gibson, which we both agree is a little bit too busy. (Maybe we should do a spin-off Robo Hunter podcast to deal with more Gibson throughout the years…)

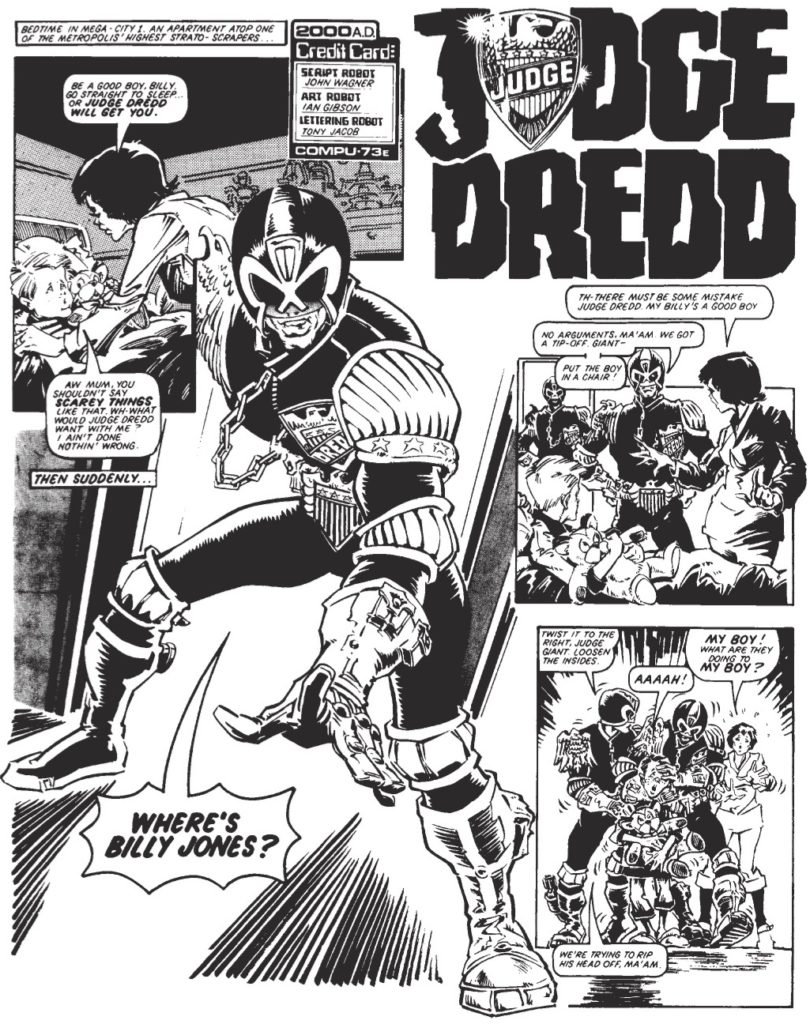

1:21:17-1:30:51: We talk about our favorite stories from the collection; I talk about the Dream Palace done in one, which Jeff likens to The Spiritstory about Gerhard Shnobble, while he can’t resist tales about Billy Jones, criminal apes — with me forgetting the name of Harry Heston in response, to my shame — and, of course, robots that want to rise up and free themselves of the shackles placed upon them by their makers. (Updated to add: Harry Heston was created by Stewart Perkins and Jake Lynch, as Henry Flint corrected me on Twitter.)

1:30:52-1:38:06: Another brief diversion, as we talk about whether or not the “Robot Wars” storyline scared creators off longer storylines for awhile afterwards, and whether “Luna-1,” the status quo change that ends this volume, is an attempt to pretend to have a continued storyline without actually going through with it. Also under discussion: The workload involved in making a weekly comic without break, and Jeff and I discovering a connection between 2000 AD and American Golden Age comics that we didn’t know we knew about.

1:38:07-1:52:14: Sure, it’s the first volume of the series and it’s the first Dredd stories, but is Complete Case Files Vol. 1 a good place for newcomers to start? Jeff says maybe, depending on what they’re looking for — dropping a Bob Haney reference in the process — while I’m unconvinced, instead likening it to the earliest issues of Fantastic Four. High praise, or merely a sign that the best is yet to come? Why not go with “both”?

1:52:15-end: We wrap things up with a truncated farewell (There was more cut for crackly audio purposes), but what you’re missing is that Drokk! will be back next month with the second volume, which brings both “The Cursed Earth” and “The Day The Law Died,” and really kicks the series into high gear. In the meantime, there’s a Tumblr, Twitter, Instagram and Patreon. Grud!

For those looking for a direct link to the audio: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp1.mp3

I think I’m going to really enjoy this series, if this first episode is any indication. As much as I love the Fantastic Four and enjoyed Baxter Building for its analysis of storylines and different creators’ artistic peaks and valleys (while pressing my nostalgia buttons), I’m much more intrigued so far by this deep dive into a property and a publishing scene I know very little about. I agree that a little more plot synopsis would be helpful, for the bigger mega-epics, at least. My one carp is that I had to eventually pause the episode and Google what a “prog” is (even though it’s fairly clear from the context). I’d love to know the why and how behind the usage of that term.

Okay, is there a story somewhere of how/why Bill Ward ended up drawing that Dredd strip? It seems rather strange

Volume 2 is probably an easier introduction for new readers more used to a longer-running storyline. In particular the Judge Cal story pretty much covers everything a new reader would need to know. Volume 1 has a lot of good stuff but it’s definitely shakier material than that follows. Great podcast, chaps.

First, this was really good stuff.

On the whole “Aren’t foreigners funny?” racism of it all — one could spend a long time unpicking how that fits into the long slow crisis of British, esp. English identity, in the postwar period. (Obviously, the complexities of national identity with regard to how England relates to foreign countries are no longer in any way a problem and this is not topical at all from a 2019 perspective,)

And of course, this is coming out of a scene dominated by war comics in which encountering people with funny accents and then shooting them was the routine. It’s very much something appealed (I hope not appeals) to children. I remember reading a old book on political socialization in western Europe (some time after this, but the book was, if I’m remembering correctly, from the early ‘80s, so the research would have been done about this time or not long afterwards). One thing it indicated was that children acquired their sense of which foreign nations were good and bad much earlier than they could relate that to the history. I specifically remember that British children knew that Germans were supposed to be bad and Americans were supposed to be good before they knew anything about the Second World War (let alone the First) – they acquired the attitudes first and the historical knowledge to inform them later.

But here’s one thing that fascinates me about Dredd: he’s a foreigner himself. It’s really odd that this character who is, as Graeme McMillan says, almost certainly the most important single thing to come out of British comics and is an iconic British character isn’t actually British — he’s American. (Am I the only person who has difficulty imagining Dredd’s accent?)

At this point, one has to note that John Wagner lived in the US until he was 12, and after that grew up in Scotland. (Plus he has a German name. There is no way that he wasn’t teased about that when he was a child.). This is liable to make someone highly conscious of national identity as an issue, I think.

It also makes Wagner very different from Pat Mills. Wagner has talked about how he feels that moving from the US to Scotland placed him in a more disciplined environment, and that this was a good thing that more-or-less saved him. It’s quite difficult to imagine Mills ever describing discipline as a good thing like that, especially in the context of school-aged children. I find it very hard to resist seeing a lot of Wagner’s background in Dredd, a fantasy about an undisciplined sprawling American urban world which is kept in working order solely by being under uncompromising control by a figure who more-or-less embodies discipline on any level. Especially in that iconic description when he comes back to Mega-City One: “..,the most violent, evil city on earth. But God help me, I love it.” (the first really memorable line in Dredd, I think).

I think that an important aspect to how Wagner writes Dredd is that he’s not the good guy — but he’s not the bad guy either. And yet he’s not “complex.” It’s that Dredd sort of sidesteps the good guy/bad guy dynamic entirely. Going out on a limb, I feel that there might have been some strict schoolteacher (presumably long since dead) from Greenock in the 1960s who, deep down somewhere inside John Wagner, might be the real Judge Dredd. (Scotland still had corporal punishment in schools at that point, which might not be irrelevant.)

Our hosts were very good on how the citizens of Mega-City One are basically idiots with no impulse control. Which is to say that they’re *children*. Dredd is the grown-up disciplinarian who is in control of a much larger number of children, which is a situation that maps primarily onto the classroom in normal real life (and is therefore perfectly suited for a child to latch onto – Dredd’s world feels psychologically real to a 12-year old).

Obviously, Judge Dredd is only very thinly set in a future America, though. This is something that I only fully grasped after moving to the US myself. Instead, it’s set in a future version of America as it appeared in pop culture from a British perspective: big cities, cops, lots of multilane highways. (The identification of the US with big cities, especially New York, is a very European thing, and contrasts with the ambivalent way in which Americans themselves define the relationship of big cities to American identity, which is often located in small towns in opposition to the big city.)

That, via Wagner’s earlier One-Eyed Jack, Dredd’s ancestor is Dirty Harry, is well-known. But note that One-Eyed Jack is itself in its title a Western riff. And the Western influence is there well before Luna-City One: Dredd is routinely referred to as a “lawman” and stories often turn on shootouts determined by who can shoot first. Mega-City One is simultaneously a violent urban hellscape and a sort of untamed Western frontier in need of (you guessed it) law, pretty much exactly as in a Western. And all the very concretely depicted others that are beyond the boundaries of “normal civilized” society: the mutants, the Troggies, etc., — I’m afraid that these are fairly clearly stand-ins for the way that Native Americans are depicted in Westerns.

So, primarily ‘70s cop films and shows (I would include self-consciously “gritty,” “modern” and “like the Americans” British products like The Sweeney and The Professionals under this heading) mashed up with Westerns in the future, but with all sorts of other bits of Americana-from-a-postwar-British-perspective thrown in there: America as the country with all the big cars, America as the country from which there is always some new technological product, America as the country from which films come…

And layered in with that, the Mikado trick, where you set something in a foreign country as a parody of your own: there’s something in the robots, for instance, which connects with the way in which British cultural products can find endless interest in dissecting class as an issue. (Which is another area where I don’t think Mills could ever have written what Wagner does. For Mills, Call-Me-Kenneth would have to be a hero, because Call-Me-Kenneth hates the right people. Cf. Mills’s uncomfortably starry-eyed naiveté about the IRA.)

And I really think that all this has to be to some extent about the way in which Britain went from being the most important country in the world to being part of a world in which America was the most important country in the world, that love/hate relationship between the former imperial power and its replacement, the ally whose language it shares and whose culture can therefore so easily penetrate its own. About the consequences of that for British national identity — or more exactly, about how that affects the way that Britain relates to images of America in British pop culture.

But I think Wagner was the perfect writer for all this, because it’s also about leaving one country when you’re old enough to grasp what that means, but not so old that it makes you forever an expatriate — leaving it because your Scottish mother split up from your American father after an unhappy marriage — leaving a country that you identify as a chaotic environment where you were always getting into fights and in trouble for a country that you identify as a secure and orderly environment, and yet being inevitably interested in the country that you left behind in a way that’s different from being interested in an entirely foreign country, and being able to access an outsider’s perspective on the country that you’ve joined in a way that only someone who is conscious of having joined it can do.

—-

On the “He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother” thing. I loved that, because it’s such a 2000 AD note — throwing in a stupid joke exactly when you’re not expecting it. That sense of not caring one little bit about tonal coherence, and daring the reader to object. One thing I’ll note is that while the spirit of 2000 AD in this period might be punk, it’s not written *for* that audience — it’s written for 10-year old boys whose parents are probably not going to let them play “White Riot” at high volume, and certainly aren’t old enough to go out to hear it live. The references are often based on the sort of universal cultural property that pretty much everyone can recognize, and for a child, that’s very often your parents’ music. Even from the ‘80s, I can remember a bit in 2000 AD that was based on the Rolling Stones.

—-

It’s interesting how Dredd develops its own memory of itself, and what it chooses to remember and what it doesn’t.

I started reading a few years after this. I can’t be sure exactly when, because it started with a friend lending me his huge stack of 2000 AD’s, which I read out of order, so I’m not sure what was the earliest Dredd that I read. (I remember that Child Me really liked Meltdown Man. Shut up. It had animal-people in it.)

There were certain elements of these late-70s stories that ‘80s Dredd consistently remembered as having happened. I knew that the Robot Wars had happened, that there had been a Cursed Earth saga, that there had been a Judge Cal. But at least in my memory, the long Luna-City 1 sojourn was completely edited out — there was no hint that anything like that had ever happened.

I just wanted to point out that this was a great comment. I didn’t know that much about Grant’s background but it makes sense with what he was creating at the time.

Thanks for the nice words. After writing the above, I became curious and looked into Pat Mills’s schooldays — and, whoa, is there stuff there!

Also, he was at school with Brian Eno. I do not find it hard to believe that this person (the tambourine player) was shaped by the same environment that produced 2000AD: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=MAVtZRI2frw

I second the praise for this comment. Great, great stuff that clarifies things for this American reader.

Quick disclaimer: I’m not actually British. I’m from Ireland, and have lived in the US for quite a while now, since the 90s. That means I’ve spent a lot of time in Britain, have British relatives, grew up exposed to British culture — or more accurately British media, which is to say London media to a very significant extent.

But Britain is a very big, complicated, place and I’m still speaking as an outsider. Just one who had a closer vantage point than some from which to observe.

This was an especially brilliant comment/set of observations, Voord, and I wish I’d been half as incisive on the podcast. Thank you!!

For those of us hoping to follow along, where can we pick these up? With Baxter Building, I just used Marvel unlimited, but less sure where to easily access 2000AD content.

We mention this in passing at the end of the episode, but the best bet is probably picking up the books via 2000 AD’s webstore: https://shop.2000ad.com/

Although they’re also available for the Kindle directly through Amazon, too. (Honestly, you’re better off getting what I believe are open-source PDFs through 2000AD, but if you already have the account with Amazon and are interested in the path of least resistance.)

Please keep in mind this is one of the few cases where being available for the Kindle does *not* mean they’re available as well in Comixology. It’s native-Kindle stuff and best viewed with a very good tablet.

I’d like to advocate for checking out the kindle previews first. the early volumes were formatted horribly

2000ad did actually miss a few weeks of publishing over the course of it’s 40 years. I wouldn’t say that Mills created Dredd (He actually wouldn’t say that himself either). Mills definitely helped shape dredds world. He did give the Judges an ‘origin’ story as well as give Dredd a more human face with his ‘better’ brother Rico. I would say…Wagner and Ezquerra were Dredd’s ‘Parents’ while Mills was the ‘Midwife’.

What’s interesting is…US comic books started out as ‘anthology’ titles that slowly disappeared to feature one main story/character…while UK comics kept the anthology format.

Love the podcast btw. Might also be worth checking out for you guys is….

http://www.spacespinner2000.com

http://megacitybookclub.blogspot.com

and maybe the very first 2000ad centric prodcast…

Everything Comes Back To 2000AD

http://ecbt2000ad.libsyn.com/

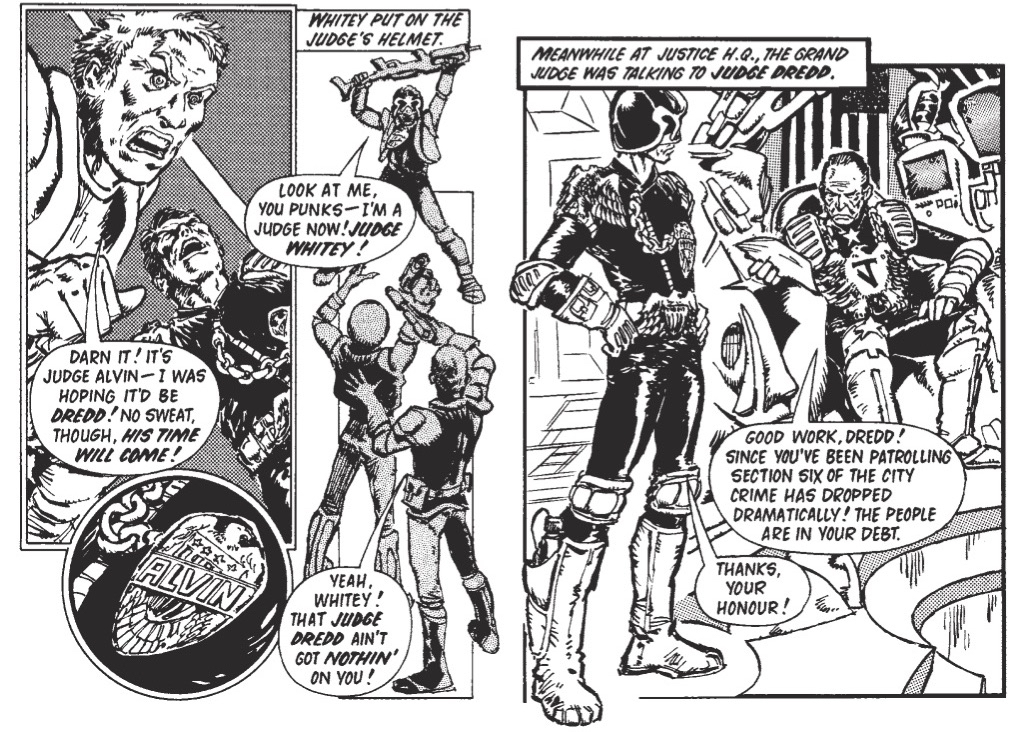

My favorite thing about the first strip, “Judge Whitey,” is that you get this great powerful shot of a judge on his motorbike right next to the logo and you think ‘oh, obviously this is Judge Dredd…’ and than the guy get unceremoniously killed.

this is a) shows how violent and dangerous the world of the strip is b) tells you that even though he his the toughest judge he is still very much a human figure, he doesn’t even have a costume uniform (just the same as all other judges), and he might die in the exact same way

Great episode! I liked how you got us to read the 340 pages then said it’s not the best jumping on point! In fact I had read the early 2000ADs when they came out as a kid. Dredd was not the standout story for me- this was Flesh! Cowboys farming dinosaurs for a future food crisis, and getting eaten by them- Dredd was tame by comparison to a 9 year old boy.

I have always felt as Jeff said that Dredd is the stability at the centre of Mega City 1 craziness and while I admire the character design I do find him a little, shall we say, one-note, but I do realise that’s the point. Reading through the case files will help get on top of the surrounding chaotic continuity.

Your outro music should totally be “He ain’t heavy…”

Nice to see Ron Turner getting some love. I really liked the Rick Random: Space Detective collection which came out about 10 years ago and is probably the easiest way to get a chunk of his work easily-ie on Amazon. If you like the thought of stylish people smoking in space, surrounded by sleek and imaginatively designed machinery, this may be the book for you. Of course, these are stories from the 50s and 60s so, unlike Dredd, when the space-faring protagonists decide to commit planetary genocide on a population with a technological level of medieval Europe because they’re standing in the way of ‘progress’, there’s no irony.

Recently I’ve been picking up more Ron Turner material in Ron Turner’s Space Ace- available from John Lawrence, who can be contacted at These are more reprints which have been coloured by John Ridgeway. It’s one of the most successful examples I’ve seen of comics drawn for black and white having colour added.

For those who’ve never seen it: Future Shock!: The Story of 2000AD is available on Amazon Prime as well.

A nice companion to Drokk!

Outstanding podcast guys! Gibson’s art does look busy in the casebook format, let alone on a tablet, as will Ron Smith’s I think, but this is a problem with the reduced page size. On the larger pages on which it was orignally published, that early Gibson busy-ness is the perfect representation of the frenetic chaos of Mega City One. Just as the colours of older American comics look deliriously super saturated when they are reproduced on newer glossy white paper, the art suffers by being moved into a physical medium other than the one it was designed for. Also, a take on “He aint heavy, he’s my brother” ….. what if it’s not a joke at all ? As a ten year old who’d never heard the song, I just found the line heartbreaking.

Super late comment, as I caught up with the series this month on a long trip (it’s awesome, great compliment to Douglas Wolk’s Dredd Reckoning blog, as stated). In regards to Wagner’s relationship to Dredd, I was thinking of something to piggyback on to the excellent comment from Voord 99. This is from the 40 year 2000AD Q&A with Kelly Kanayama. Wagner was asked if he sees any characteristics of himself in Dredd (and Strontium Dog) and he replies, “I do put a lot of my own words and thoughts into Dredd, but then I also have to think a bit outside myself to give him just that added edge. I suppose I’m just a harsh, unpleasant person. I make few allowances for human frailty.” The last two lines are said more as a joke, but I still think it reveals a lot.

https://youtu.be/BXQesN7z9EM?t=1540

At some point reading early Dredd, it seemed to me that the strip has more influences from Logan’s Run and Death Race 2000 than I’ve ever read anyone comment on. Like, his gun has to be a straight steal from Logan’s; in the book version at least, Logan has a selectomatic six shooter loaded with rounds that all do a different thing, including an explosive charge like a Hi-Ex, if I recall correctly (I don’t know if it’s in the movie). And Dredd’s origin as a government project cloned from the best of the best is quite close to the protagonist’s in Death Race. There’s lots of similar themes and subtexts in all three; of course there’s lots of differences too, one of them notably being that Dredd doesn’t have a character arc that ends with him tearing down the fascist regime that he was programmed to serve. I know that Wagner’s softened him up a bit as the mutant rights and democracy subplots have gone on over the years, but I’m not versed enough in the strip to know how far that goes.

And in Death Race 2000, Frankenstein’s emotional detachment from everything outside winning the race is not too far from Dredd’s commitment to the Law. He has a key line of dialogue that goes something like, “The pursuit of excellence is all we have left.”