Previously on Drokk!: After a somewhat uneven first couple of years, Judge Dredd as a strip has settled into somewhat of a groove as co-creator John Wagner took full control of the writing chores and set about transforming the series’ setting Mega-City One into an important character in its own right. Who would want to separate Dredd from Mega-City One at this point?

0:00:00-0:02:46: With the kind of rustiness that comes from not having recorded a Drokk! in awhile, we stumble through an introduction that explains that, this episode, we’re covering Judge Dredd: The Complete Case Files Vol. 4, covering 2000 AD Progs 156 through 207, running 1980 through 1981. But before we get too meander-y, I have a question for Jeff…

0:02:47-0:09:59: Is Vol. 4 a collection full of re-runs and deja vu? We discuss that Judge Dredd as a serial has been around for long enough to have a history, and the drawbacks that brings — namely, that there’s now the opportunity (taken often in this volume, it feels like) to repeat ideas and storylines, as well as merely reference them, although that happens as well. Aw, Judge Dredd, you’re old enough to have continuity now…!

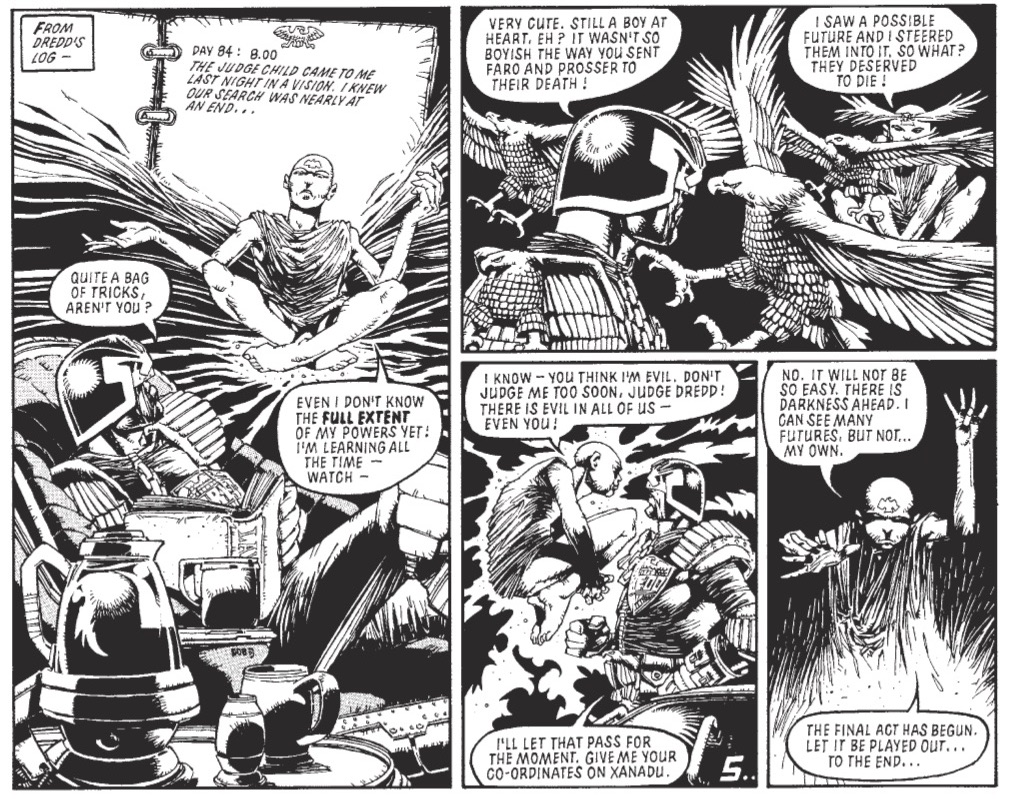

0:10:00-0:25:36: In response to my question, Jeff brings up his theory about a running theme in this particular collection: The importance of free will, and the lack of free will when it comes to the characters in Dredd. (Well, outside of Owen Krysler, AKA the Judge Child, and Dredd himself, perhaps.) Is Wagner arguing that people can only exist within the confines of their character, but that their characters are purely defined by external influences? And we’re not talking about those external influences being the Judges, either… They might be as trapped as the rest of the citizens.

0:25:37-0:38:38: Another potential running theme is Dredd as both contrarian to everything around him, but also as an unchanging monolith that everything and everyone else has to work around. But is that a problem? Both Jeff and Judge Macgruder think so, but Jeff goes so far as to suggest that it might be a particular problem because Dredd doesn’t have any control over his own actions because he’s been programmed into being a machine — something that this volume in particular isn’t shy in presenting a case for.

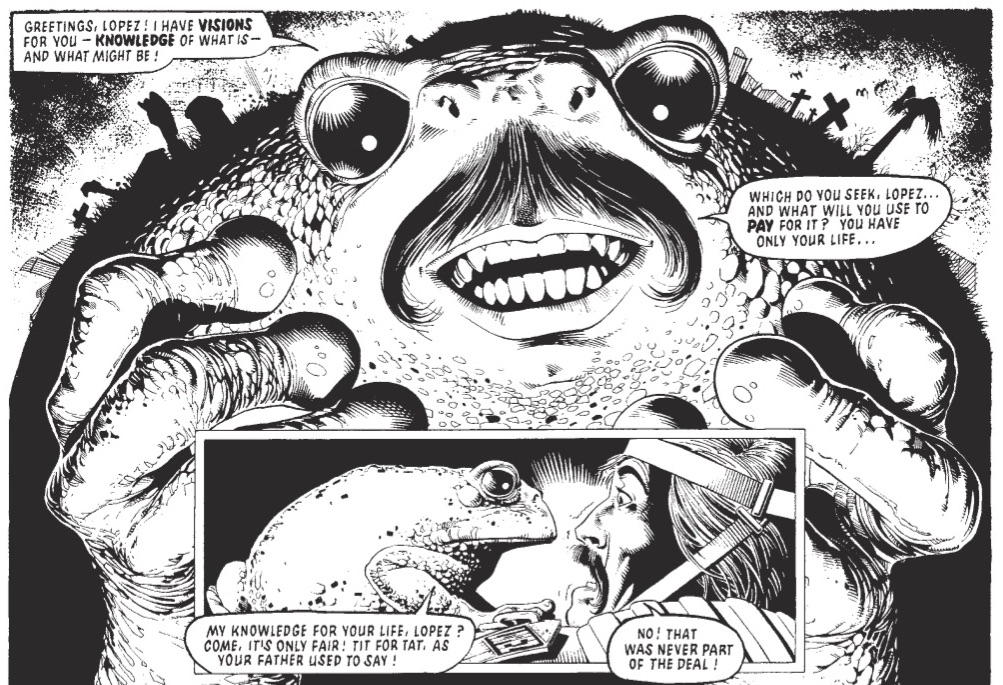

0:38:39-0:51:29: It isn’t just questions of free will that this volume is obsessed with; I also think it’s an era of the series that is focusing on satirizing (and criticizing) consumer culture, with the return of Otto Sump and televised war games being the most obvious examples. In response, Jeff brings up the work of Italian director Segio Corbucci, whose spaghetti westerns presented a particularly bleak worldview that may also have informed some of the episodes of the strip on show here, especially in the Judge Child storyline.

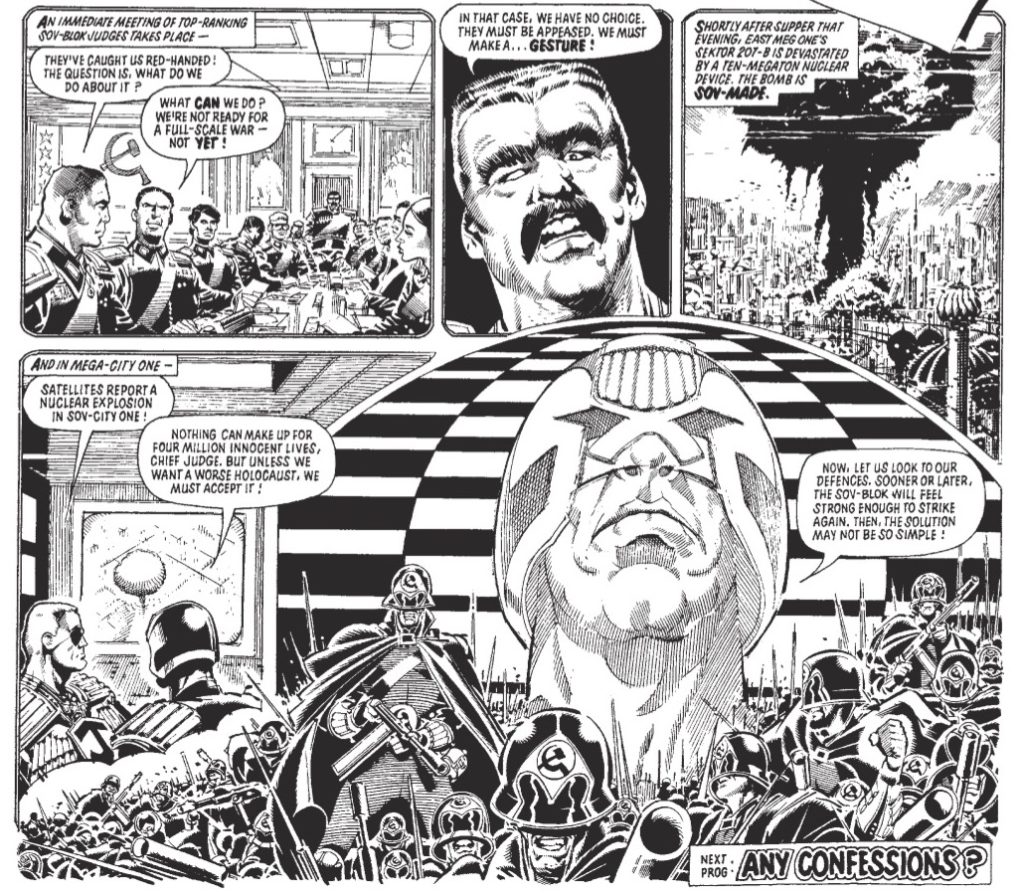

0:51:30-1:08:19: There’s always been an undercurrent of dark humor in Dredd, but does this volume represent a new level of that? Nuclear apocalypse and body horror fuel some of the “weird darkness,” as Jeff calls it, in these episodes, with Basil Wolverton and Ken Reid being referenced as potential influences on Ron Smith’s artwork in particular. We also discuss the morality (or lack thereof, potentially) in Dredd as a character, whereas he may be the most moral character in the series but that doesn’t mean he’s especially moral — especially when it comes to passive aggressive confrontations with other Judges over facial hair. (Not mentioned in the podcast, but I’m mentioning it here: Dredd also has a real problem with accountants, and appears twice in this volume.)

1:08:20-1:19:44: Has John Wagner created such a unique tone to the series at this point that no-one else will be able to capture it? We talk about the future evolution of Dredd, and how it impacts the work of future creators when it comes to working on the character, and then we talk about the seeming lessening of the parallels between this strip and Will Eisner’s The Spirit, which has become somewhat of a running theme on this podcast.

1:19:45-1:31:48: There are a lot of new characters introduced in this volume who’ll show up again in the future, bringing about a discussion about supporting casts both in Judge Dredd as a strip, and British comics in general. Did British comics, historically, not really care that much about character because there wasn’t enough space to include anything other than plot and high concept?

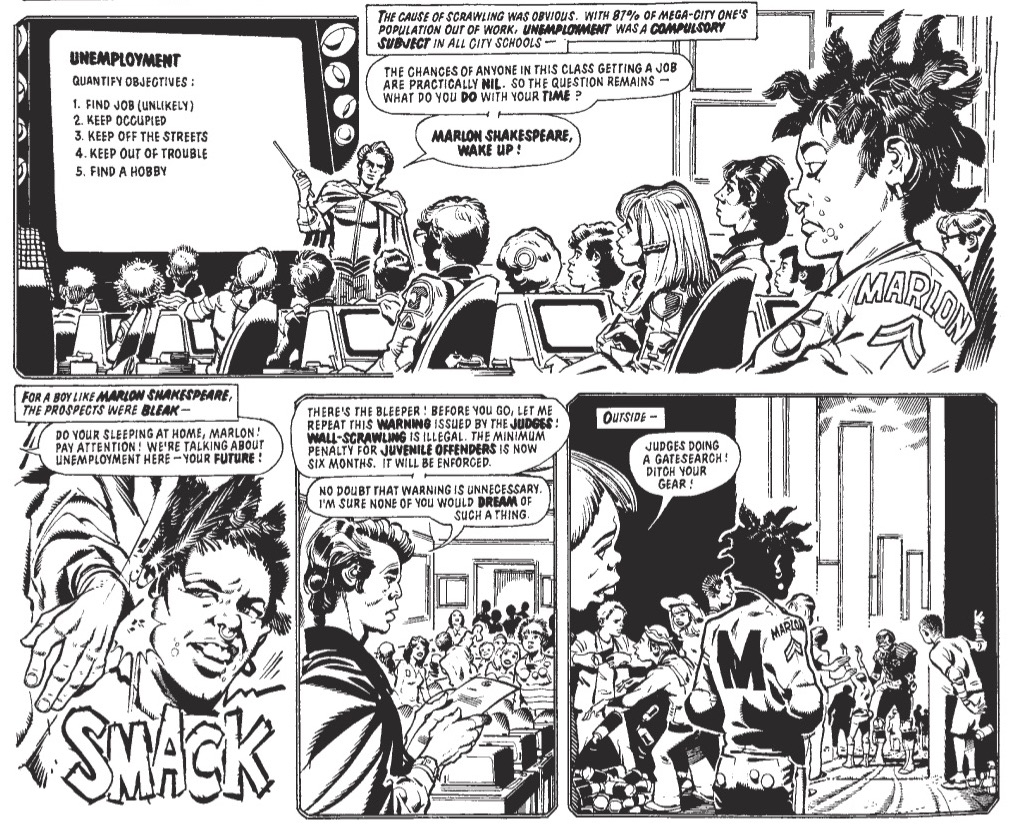

1:31:49-1:39:18: For a comic that has often been referred to as being particularly punk rock, this volume of The Complete Case Files gets punk pretty wrong, borrowing a lot of the surface imagery but surprisingly little of the underlying attitude. I refer to it as a Bob Haney version of punk, which feels odd given the timing of both 2000 AD’s launch and these strips in particular, but perhaps we’re reading too much into Ron Smith’s aesthetic as a whole. There’s also a slight reprise about the free will question, thanks to the conclusion of the “Unamerican Graffiti” storyline that prompted this particular diversion.

1:39:19-2:00:01: We get into our favorite stories in the volume, with Jeff choosing between “Unamerican Graffiti” and “Loonie’s Moon,” and my choices being either “Pirates of the Black Atlantic” and “The Fink.” While we’re at it, we talk about foreshadowing what’s to come, whether it’s creative legacies of these stories — you can see shades of future 2000 AD and Wagner/Grant collaborations at times — and also stories that are about to show up in the Judge Dredd strip as a whole. Also, I come up with a theory about how the strip treats animals versus humanity.

2:00:02-2:05:02: We quickly wrap things up for the episode, mentioning that we have Tumblr, Twitter and Instagram accounts, as well as the Patreon account that makes all of this whole thing possible — and then there’s the fact that, next episode, we’re literally heading towards nuclear armageddon in a storyline that’s actually called “The Apocalypse War.” So, you know, good times ahead, I guess.

For those looking for a direct link to the episode, here it is: http://theworkingdraft.com/Media/Drokk/DrokkEp4.mp3

Mean Angel is the nice one (until they cyborged him), Fink lived in a hole because he wanted to.

I really don’t like the Angel characters, we are repeatedly told they are these dangerous criminals, but whenever we see them in action they use completely idiotic methods that should have gotten them killed immediately. This would be fine for a character only appearing in a single 8 pager, but now we are subjected to these sorry excuses for a super long story and then they keep coming back again and again.

I’ve been thinking about Dredd and punk since you first brought it up, but this episode gave me some clarity. This past year, I started reading through the Dredd Case files, while at the same time making my way though “Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984” by Simon Reynolds. I didn’t make the connection until I started listening to Drokk, but both the first few Case Files and Reynolds’s account of the British post-punk scene cover the same period from the late 70s through the early 80s. Reading both made me think of Wagner’s Dredd as way more post-punk than punk, at least in terms of the way that Reynolds defines the distinction.

There are plenty of parallels. There’s the science fiction imagery, and the idea of people as robots; the parody of commercialism through grotesque exaggeration; the sense that Mega City One is like a post-industrial society, where everybody has lost their jobs to automation, and has descended into either hedonism or nihilism.

The post-punk lens also helps explain the weird relationship that Dredd has to fascism. There’s always this push and pull, where Dredd’s violent oppressive methods are depicted as alternatively terrifying, and the only way to maintain order. Similarly, punk bands may have used Nazi imagery for shock values, but bands like Joy Division took the interest in fascism to a new, morally questionable level (though they later distanced themselves from it).

I think it also helps define the distinction between Mills and Wagner. Mills is punk all the way, while Wagner is post-punk. It’s obviously a simplistic distinction, but I think it helps explain why Mills never got a handle on Dredd. Mills is too earnest committed to his anarchic ideas to write a character who’s a weirdly sympathetic fascist.

Anyway, thanks for another great episode. I can’t believe the Apocalypse War is already next episode. Looking forward to it.

My reaction to this volume was a little more positive than our hosts (who were pretty positive.) Nostalgia is probably a lot of that — this is about where not just the mature Judge Dredd starts (as Graeme McMillan points out) but also my personal Judge Dredd.

Somewhere in here was the earliest story in the big pile of 2000 AD’s that my friend lent me when I was a child. Although I don’t remember it this way, there were clearly big gaps in his collection — I didn’t read the Apocalypse War, which comes after this, until much later. But there are stories here that I know that I read as part of that huge disorganized pile, such as the one with the fear gun (which made a big impact on my very young self).

However, I was *far* too young, certainly, to appreciate how rich these stories are, and I do think they are very rich indeed.

While our hosts are admittedly correct that we start revisiting stuff, I think that this is one of those cases where variations on a theme serve to make the critical differences more salient.

Graeme McMillan detected the possible hand of Alan Grant in the satires of consumer culture in this volume. On that topic, Jared made an interesting and convincing argument in the comments to the last episode, in which he suggested that the key element in producing the “protagonist but not hero” Dredd for whom our hosts have been looking was Grant entering the picture.

I think you can see more evidence for Jared’s argument in the stories in this volume. Not so much immediately when Grant joined, but from Get Ugly on.

Jeff Lester’s comments on Alone in a Crowd are a case in point. There’s a new interest in the idea that the Judges are an oppressive presence, no different from a tap gang from the perspective of the ordinary citizen of Mega-City One.

Another thing is when Wagner writing with Grant produces a very different portrayal of the Crime Blitz from Wagner writing alone in its original appearance, in which the point was very much to kick off a story in which Judge Dredd was a conventionally heroic James Bond figure, and the Crime Blitz was a device to set up the paradox of the spy who was too innocent. Now we have a real focus on how horrific it would be to be subjected to a Crime Blitz.

Another shift that I think one can detect – visible before Grant arrives – is a shift away from “Mega-City One=America-in-pop-culture-viewed-from-Britain” towards Mega-City One being its own bizarre space which can be British when it needs to be. This becomes obvious in the Cursed Earth segment of the Judge Child Saga, because it’s the area outside Mega-City One, especially Texas City, that’s defined as a satire on America in contrast to Dredd, who seems normal (=British) in contrast.

There’s a really telling bit of dialogue in the Memphis story. We have a slave-auctioneer dressed as Uncle Sam who says “Faro may be crazy, but he owns ten thousand slaves and most of the land round Memphis – and he don’t take kindly to lawmen!”

And Dredd responds by thinking, “If I blow the gaff too soon…” Perhaps the least American dialogue imaginable, especially in contrast to the language that prompts it. Various other bits of dialogue reinforce this sense that Mega-City One is somehow British. For instance, Chopper calls his mother “Mum.”

Other scattered thoughts:-

-I call that character Chopper, because that’s who he is in my head, but in Un-American Graffiti it’s actually rather important that he’s *really* Marlon Shakespeare. That story is probably the quintessential example of something I absorbed as a child (and without being too pompous about it, might have been a good influence on me) without really appreciating just how wonderful it was. There’s so much good stuff in that story, such as the way it exploits comics lettering on the page as graffiti.

-And it might be a mark of Grant’s influence that Marlon/“Chopper” is very much an anti-Dredd figure, and is also not only the central character of the story, but a real hero — if we lay aside Walter as essentially comic, I think Marlon might be the first character in Judge Dredd to beat Dredd and triumph at the end of the story?

-Un-American Graffiti also the first piece that I think you can definitively identify as anti-Thatcherite. By this point unemployment the UK had risen to unprecedented heights. The whole notion of schools that have classes to prepare you for unemployment is the best single piece of satire that we’ve seen so far, and aims itself really nicely at how the education system destines one set of people for “success” and another set of people for “failure.”

-Which brings us back to Chopper being the anti-Dredd, and Judge Dredd as a story being about school. I really liked what Jeff Lester observed about how Marlon defies the forces confining him into being the product of his background.

Our hosts commented on the recurrent idea that Dredd’s choices are predetermined by his background, which has made him an inhuman machine. However, what I’d like to draw attention to in connection to that is that it’s not just Dredd’s background. It is over and over again stressed that it’s the Academy that’s made Dredd what he is and not (for instance) his years of experience on the streets of Mega-City One (which would be the more normal cop drama cliché).

-So as Wagner (reinforced by Grant?) becomes more relaxed about Mega-City One being able to be Britain, he increasingly emphasizes that Dredd is the product of an exclusive childhood education characterized by separation from contact with one’s family, uncompromising discipline, and the suppression of emotion as weakness, an education that makes you a superior class of person who occupies the top of the power hierarchy. Well, I can’t imagine any relevance that has to British life at all.

The interesting thing, though, is how sympathetic the stories are to the idea that going to the Academy really does make you special — that it’s just wonderful that Dredd is a machine.

-An aspect of this is that Dredd isn’t necessarily that special to other judges. When our hosts commented that Judge Hershey isn’t really characterized but somehow feels like she’s a real person, it occurred to me that part of that might be that Hershey serves to make Dredd himself feel real, because she views him in a matter of fact way as another judge — a senior and important one, but no more than that.

-Of course, one can’t underrate how distinctive it was at the time to characterize any female character as a capable and intelligent professional and just that.

-Aside from unemployment, the other element that really stands out to me as a quintessential part of British culture in the early ‘80s is the salience of nuclear war. This was the era when CND was ramping up its protests – I think the first ones at Greenham Common happened about this time, although the Greenham Common women weren’t really a thing yet.

Things like the acerbic “Today we’re talking about how to survive nuclear attack” sequence — the very specific description of the nuclear explosion and its effects — the half-sympathetic, half-not way that Jenno Matryx’s hard but wrong decision is handled — these things are snapshots of a facet of what it was like to be alive in the early ‘80s: the awareness that at any moment you might not be.

But maybe not everywhere. I’ve been struck when conversing with Americans of about my age how much less salient the terror of dying in a nuclear explosion, or from radiation sickness, seems to have been for them as children than they were for me and other Irish children in my age-group who consumed British media. Obviously, Americans were aware of the possibility, but it does not seem to have been as dominant a concern in US culture, despite the fact that the US would have been, for obvious reasons, the highest priority target of Soviet ICBMs if there had been a nuclear exchange, and that a nuclear exchange would have taken only the slightest of misunderstandings on either side of the other’s intentions.

Certainly, I don’t think you’ll find as much interest in the likelihood of nuclear annihilation in superhero comics of this period as you do in 2000 AD. I think there’s something in that difference about the British experience with strategic bombing in World War II — 2000 AD is reproducing the memory of a historical experience that sensitized British people to their vulnerability to sudden death from above.

Jeff Lester has laid out an interesting and compelling argument about the rise to dominance of the MCU as being about American’s difficulties with experiencing vulnerability on 9/11. I’d maybe add that, perhaps, this reaction to the jarring and unexpected realization of American vulnerability is in part because Americans didn’t, for better or for worse, grow up reading things like Pirates of the Black Atlantic?

To reiterate Voord 99’s post, the Dredd of this period was very much influenced by the attitude behind the “Protect and Survive” public information films made by the government in the late ‘70’s/early ‘80’s which had a huge impact on contemporary pop culture:

https://youtu.be/6677Eppc-sk

You didn’t mention it here, but after the Judge Child story, the writing credit switches from “John Howard” to “TB Grover”, both of which are of course pseudonyms. The switch is around the time that “John Howard” has won the Eagle award for best writer, and there are quite a few letters complaining about the switch, calling for Howard’s return and disparaging Grover. This is compounded by them running a Tharg strip where the Howard droid starts malfunctioning and is put out for scrap, plus antagonistic replies from Tharg to the letters where he says that Howard was past it. This would all seem a bit harsh to readers who believed John Howard to be a real person distinct from TB Grover!

Do you think there have been any comics that have been effective at capturing the idea of “punk”? There have been a few titles in recent years that have been, at least on the surface, about punk, but none of them seem even remotely like the punk scene/community/ideas that I’m familiar with.

It’s not about the period, but there’s something about the feel of ‘ The End Of The Century Club vol 1’ by Ed Hillyer that rhymes or resonates.

FWIW, I’m an American who was born in ’76, and we even did some of the nuclear drills of hiding under our desks. The threat of nuclear annihilation hung over our heads, but perhaps, as you point out, it wasn’t as palpable as in the UK. I will say two things though: There was almost an audible sigh of relief that went up after the Berlin Wall fell, as we didn’t think the nuclear apocalypse was likely any longer. (Look how quickly Hollywood dropped Russians as the baddies from movies in the ’90s.) Two, Americans, I think, always believed they would come out on top in a nuclear war despite all the evidence that no one would. I would say Americans were alway paranoid about a full-scale Soviet invasion, even though distance would make that somewhat of an impossibility.

That’s really interesting. Especially the part where you comment about American interest in Soviet invasion,

This is going to be very relevant to the Apocalypse War (in our hosts’ next episode!), in which we do have a Soviet invasion, and yes, the Americans do come out on top in a nuclear war.

Just a few thoughts on this volume of Judge Dredd.

-This may have been my favorite volume to date, or at least on par with vol. 3.

-“Knock on the Door” may not of been the best of this bunch, but the tone and the way Dredd behaves encapsulated what I always thought to be quintessential Dredd, prior to joining this read through that is.

-Ron Smith, Mike McMahon, and Brian Bolland are by far my three favorite Dredd artists. Ron Smith is my out and out favorite. The acting and facial expressions are some Wally Wood-level goodness. I think McMahon does aces when the story has a horror tinge, and I think I actually pumped a fist in the air when I saw he was the artist on the necromancer story.

-The quality on display here is just breathtaking. Give this book to almost any comics fan unfamiliar with Dredd, and I bet they wouldn’t be able to tell you they were made in the early ’80s.

-Loved the discussion of the underlying themes of free will.